Lakagígar

The Laki Craters on Iceland

About the eruption of the Laki fissure in 1783 & 84 and the effects the eruption had on Iceland.

History

Today we have a fairly accurate description of the effects of the Laki eruption in 1783–1784, thanks to a nature-loving preacher living in southern Iceland at the time, Jón Steingrímsson. It is thanks to Jón’s writings that the eruption has been the subject of research and literature ever since.

My description from Jón’s point of view is based on the books »Island on Fire« by Alexandra Witzke & Jeff Kanipe, Pegasus Books 2014 and »A Mist Connection« by Katrin Kleemann, De Gruyter 2023.

This fissure eruption is considered to be one of the largest documented eruptions in Iceland to date. It is remarkable for the amount of lava and poisonous gases ejected, the duration of the eruption and, above all, the effects far beyond Iceland.

It was named after the over 800m high Laki volcano, which had erupted on the site long before (4550 BC) and on whose flanks the fissures of the Laki volcanoes opened. The volcano itself had not become active again. In Iceland, not only the name Lakagígar, but also the name Skaftáreldar (Skaftá Fire) has stuck, because the first sighting of the lava fountains was at Skaftá and the first course of the lava flows was directly connected to the river.

The early phase

In May 1783, the inhabitants of Kirkjubæjarklaustur (Klaustur for short) noticed a number of earthquakes and blue smoke drifting through the air.

On 8 June, residents saw the first fires in the sky north of Klaustur.

Ash kept falling from the sky and fog clouds moved in from the north.

The following days, ash continued to fall from the sky and darkness fell over the landscape. Fog and rain appeared corrosive and irritated eyes and skin.

From 9 June the river Skaftá began to dry up.

10 June 1783 strange dry fog clouds were recorded in Bergen & Trondheim in Norway.

The 1st active break-out phase

12 June 1783. After the water in the Skaftá River had failed earlier, lava suddenly came through the Skaftá Gorge, which lay to the west of Klaustur. It flowed quickly and flowed into the wetlands and other smaller rivers. The connection with water led to explosions again and again. At first, the lava followed the riverbed, but later it came over the riverbank and spread over old lava flows, pastures and farmland.

On 14 June, ash fell from the sky. Jón wrote: »It was blue-black and glistening, as long and thick as hair of seals.« What Jón described then is what volcanologists now call »pele hair« — thin ribbons of volcanic glass that came from molten rock that had been drawn into length to form fibres during lava fountains.

The following day, a few farmers had decided to climb Mount Kaldbakur, 8 km north of Klaustur, to get a possible view of the eruption site. They reported lava flowing into the gorge and far away in the greater distance they had counted 20 fire fountains shooting high into the sky!

In the last days of June, the lava flow turned southeast and engulfed pastures and forests and devastated farms and churches. Birds fell dead from the sky and fish floated lifeless in rivers and lakes. Earthquakes continued and poisonous gases filled the air to breathe. Drinking water had become undrinkable from sulphur and fresh water pools were polluted with ash.

The lava continued to move eastwards along the Skaftá riverbed between 13 and 19 July 1783. It began to threaten Klaustur and with it the church of Jón.

Sunday, 20 July 1783. For 42 days and nights the eruption had threatened the people of Klaustur and the lava flow had not reached the sea as they had hoped. Jón is said to have preached an angry sermon in his lava-threatened church. The lava flow stopped and dried up outside Klaustur that day, and Jón went down in Icelandic history with his nickname »Fire Priest« (Eldprestur).

By the end of the first phase, the 200m deep and 60m wide Skaftá gorge had been completely filled from a series of volcanic vents west of Mount Laki. The lava had penetrated far into the lowlands south of Klaustur and travelled over 60 km from the eruption site.

The 2nd active break-out phase

Shortly after Jón’s »Fire Predict«, he noticed another fiery glow in the sky on 24 and 25 July, which was accompanied by renewed rain and thunder on 28 July.

On 31 July 1783, a familiar pattern repeated itself. While the Skaftá river passed to the west of Klaustur, another river, the Hverfisfljót, flowed to the east. Two days after the community members heard the sounds from the north-east, the Hverfisfljót began to heat up until it finally evaporated.

By 3 August, this river had also dried up completely. On 6 August 1783, the sixth lava flood rushed down the empty course of the river, overflowed its banks and burned or engulfed the homesteads that stood in its way.

On 1 and 10 September 1783, the seventh and eighth floods followed.

The ninth lava flow started at the end of September. The tenth and largest lava flow in the Hverfisfljót riverbed started on 25 October and lasted until November 1783.

As the lava slowly approached from the east, the inhabitants of the Síða region around Klastur feared that they would soon be trapped. To the north lay the highlands, the lava’s point of origin, to the west the smouldering remains of the first lava flows, to the east the molten lava of the last lava flows and to the south the coast; those who could still fled the area.

After November 1783, magma production decreased considerably. In December of the same year, Jón wrote that »all the flames and brilliance in the sky began to diminish.«

The new year 1784 began with milder and calmer weather, with occasional heavy frost and north winds. However, there was still a strange smell in the air. On 7 February 1784, the official end date of the eruption, local residents saw the fires of the Laki Fissure for the last time.

The »aftermath«

Volcanic and seismic activity in the Grímsvötn system, in the subglacial areas beneath Vatnajökull, did not stop on 7 February 1784. The inhabitants of the Síða region continued to hear »rumbling sounds […] from under the glacier«.

In the spring of 1784, there were two large and sulphurous-smelling glacier discharges (Jökulhlaup in Icelandic). At least four eruptions occurred at Grímsvötn volcano, two before and two after the end of the Laki eruption. Although they did not trigger further lava flows in the lowlands, they burdened the surrounding area with further tephra fall. The Jökulhlaup and Vatnajökull sounds indicate that volcanic activity at Grímsvötn continued under the ice until 1785.

The end date of this volcanic-tectonic episode at Grímsvötn was 26 May 1785. Two more Jökulhlaups occurred in May 1785 and November 1785: The origin of the second Jökulhlaup remains unclear.

The impact on Iceland

Besides the direct consequences of the lava flows, the eruption had also produced large quantities of gases and ash. The gases, especially fluorine, poisoned the fields, meadows and ponds.

Between 1783 and 1785, 50% of all cattle, 79% of sheep and 76% of horses died, as did the fish in the ponds and other animals.

In Iceland, the eruption is also remembered for its consequences: The Famine of the Mist, or Móðuharðindin. Since the Icelandic diet at the time was mainly based on meat and fish, the consequences of this outbreak were catastrophic. By 1785, about 20 percent of the Icelandic population had died of hunger, malnutrition or disease.

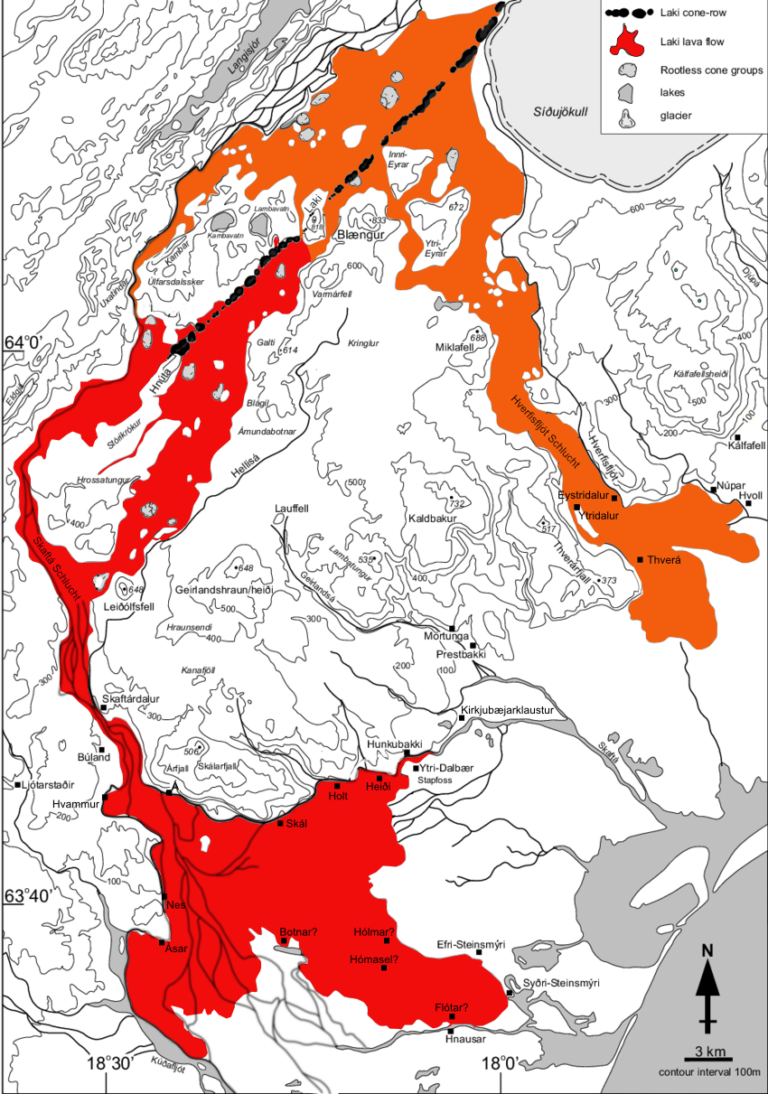

An overview of the two lava flows

The map below shows the series of craters and the two lava flows that have gripped Klaustur. The map also shows the former gorges of the Skaftá and Hverfisfljót rivers.

The original map was published by Thorvaldur Thordarson, University of Iceland. Thank you for allowing me to use it here as an illustration. I have changed it slightly to show the two different lava flows of the two eruption phases. Shown in red is the first phase from June to July 1783 and in orange the lava flow from the second phase from the end of July 1783 to February 1784.